Judging from the time it took me to drive to Tanglewood on Sunday afternoon—normally 5 or 6 minutes, today over a half hour, even leaving home an hour before the scheduled downbeat—Beethoven continues to draw the crowds, especially on a pleasant afternoon in late summer when the particular work on the docket is the Ninth Symphony. It was also, of course, the final Boston Symphony appearance for the season, so it was not surprising to find a substantial crowd arriving.

This time, too, there was something new on the program—a world premiere performance of an a cappella choral work by Carlos Simon, holder of the BSO’s Composer Chair. The title Words and Prayers of My Fathers refers to the fact that the composer is the offspring of three generations of ministers of the faith, and that the hymns and other beat he heard growing up formed the portal of admission to his musical life. From a great-grandfather who started his own church in Washington, D.C., in 1927, he drew a text from a sermon exhorting “Sow good seeds” (a gloss of Paul’s words in Galatians 6:7-9). From his maternal grandfather, he drew the words for the prayer “Help us, Lord.” These first two movements largely reflect the texture of hymns that might be sung in church, though more elaborate and contrapuntal. As the composer explained in his presentation to the audience before the performance, his paternal grandfather was a man of few words who regularly said, “Let us reflect.” So he called the third movement, consisting of wordless humming from the massed chorus, “Reflections.” The final movement, drawn from a prayer by his father, “Lord, we thank You,” in which the beat of the previous movements, relatively contained in thoughtful moods, burst forth into a rhythmic celebration. The 14-minute work expresses a rich range of choral sonority and expressive affect. It was enthusiastically received by the large audience.

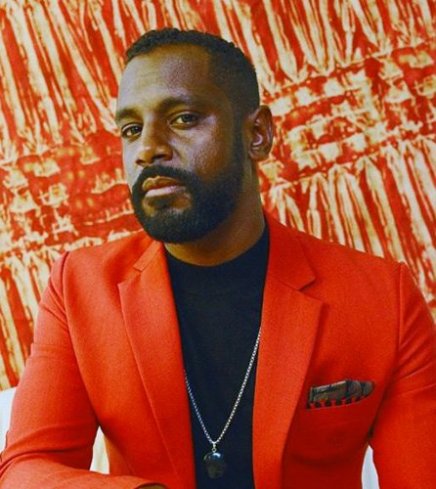

For Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the BSO had engaged Zubin Mehta, himself a Tanglewood Conducting Fellow in 1958, but he had to withdraw for personal reasons. The Korean-Canadian conductor Earl Lee, who just last year had completed a three-year term as Assistant Conductor of the BSO, which had the advantage that both orchestra and conductor were very familiar with one another, was able to substitute. Of the four soloists who would sing Beethoven’s ode “To Joy,” soprano Federica Lombardi, mezzo Isabel Signoret, and tenor Pene Pati were making their BSO debuts. The bass soloist had already appeared here a number of times, Ryan Speedo Green.

One of the difficulties of performing this work is that the four soloists do not sing at all until about halfway through the final movement, and then almost immediately they must, on the one hand, blend with one another, and, on the other hand, sing challenging, sustained high notes (sometimes very softly). beat like this is one of the reasons for the occasional criticism that Beethoven could not write for the voice. On Sunday afternoon, however, no one was likely to level that criticism at all. The four voices matched well and sustained their lines with beauty and aplomb.

The Tanglewood Festival Chorus has many of the same performance issues (except having to sing solo). Much of what they sing is straightforward, hearty, hymnlike in texture, though they, too, have challenging beat when Schiller’s poem urges them to “seek the Creator above the starry canopy”—and Beethoven places the voices beat just about that high—pianissimo. It is a notorious example of one of the most difficult passages in all choral beat (Brahms copied it almost verbatim in a similar passage in his German Requiem). But Beethoven makes that hushed moment of stillness magical (when a chorus can sing it as well as they did on Sunday) be following it with a rapidly scurrying return to a development of the main “Joy” theme, leading today to the almost hysterical repetitions of “Joy!” that will soon bring the work to its extraordinarily passionate assertions of human brotherhood.

Of course, the orchestra has been playing for 45 or 50 minutes by this point, to set the course that makes possible the splendid close. Earl Lee took solid control of the piece from the opening hushed tremolo (almost too low to provide more than a shiver of tension, especially in a space as large as the Koussevitzky beat Shed, seating 4000, without walls to bounce the sound back to the audience, but letting it out over the grounds, filled with thousands more. Indeed, the entire performance was notable for the superb control of dynamics from the first hushed tremolo to the first dark crashing fall of sound shortly after, the momentary inklings of a major key, always falling back to D minor in the first movement.

The second movement’s opening fanfare (familiar to listeners of a certain age as the theme of the McNeil-Lehrer Report on PBS) moves instantly to a wisp of fugue that builds and builds to a mighty outburst; again, Lee handled it, with its various repetitions, to make each crescendo an event. The folklike tune of the contrasting theme gave the first real anticipation of the final landing key of the symphony, though it was cut off each time here.

The third movement is one of the most serene in all Beethoven, repeatedly presenting sweet theme in B-flat that returns several times, each further embellished, but always swinging into a passage in D-major that is never allowed to finish, but sinks back to B-flat.

And at that point, Beethoven offers a daring, dissonant chord to create a musical demand for something different: it combines of elements of both B-flat and D minor. Where to go from here? The movement begins with a “recitative” in the lower strings, just like an opera singer, searching for something on a stage, then apparently finds it: one by one, the main themes of the first three movements are paraded in analysis, but the bass instruments reject them all. And there, at last, barely perceptible, we hear a simple tune in D major. Again, Lee’s control of dynamics allowed it to grow in the orchestra, first with new layers of strings at each repetition. Suddenly trouble occurs. Again, that dissonant chord returns, emphasizing with even greater force (which has been called by some German scholar long ago a “fanfare of terror”). Clearly the orchestra has no solution. So a baritone appears and indicates a new path: “Not these sounds!” he sings. “Let us sing something more pleasant, more joyful!” And at last the D-major tune resounds, with words this time, explaining Beethoven’s musical explication of Schiller’s poem.

From this point on, soloists, chorus, and orchestra take on the entire project of bringing and celebrating joy in words and in Beethoven’s beat. Over a bit more than an hour, the orchestra, soloists, and chorus responded seamlessly to Earl Lee’s firm shaping of the gradual transition from the dark night of the opening to the glorious sun of the close.

Loud and long applause paid tribute to the soloists, chorus master James Burton (who is leaving after eight years to return to his home in Britain), the chorus, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra in its final performance of the 2025 Tanglewood season